Episodic memory and spatial navigation in humans share many common neuroanatomical substrates to function, including the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex and related structures. These areas are damaged in the early stages of Alzheimer‘s disease (AD), the most frequent type of primary degenerative dementia. This is one of the reasons why people with AD may have impaired episodic memory as well as way-finding difficulty in the very early part of the disease. Without careful management or prevention, getting lost is inevitable. The mechanisms of spatial navigation impairment and consequent getting lost events, how to improve it, and its potential role as a biomarker are, however, not entirely known. Over the past years, a research team at National Cheng Kung University has been working to prove the beneficial effects of exercise on spatial cognition in people with a family history of AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI), to understand the mechanisms of this effect, and to use devices (AI) to precisely assess spatial navigation ability and to improve the compliance and fidelity of the exercise program.

With the sponsorship of Taiwan’s Ministry of Science and Technology, the preliminary results of this research team support that exercise improves spatial cognition in people with MCI and those whose parent or parents have Alzheimer’s.

Topographical disorientation or way-finding difficulties are common symptoms seen in people with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Getting lost, the consequence of topographical disorientation or way-finding difficulty, may result in unwanted accidents or even death, and hence has a huge impact on our society and increases costs. The number of getting lost events continues to rise despite the fact that devices, facilities, or security have been launched and widely used.

The mechanism causing people with AD to get lost is complicated. From animal and human studies, it has been known that place cells, grid cells, head direction cells and border cells play a critical role. Surprisingly, the distribution of the aforementioned cells in the brain fits quite well with the areas which are damaged in the very early stages of AD. This fact may explain in part why many people with AD may have way-finding difficulty or impaired spatial navigation in the initial part of the disease. In the same way, it also implies that spatial cognition can be a useful biomarker or behavioral marker for AD. Supported by Taiwan’s Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) and led by Professor Ming-Chyi Pai, a multidisciplinary team has been working on a project focusing on spatial cognition in a group of participants including cognitively unimpaired (CU), mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild AD. Most importantly, this study also invited CU people with a family history of AD (one or both of their parents). The team includes experts from the academic fields of clinical neurology, gerontology, sport science, astronautics, aeronautics, psychology, genetics, molecular biology and anatomy.

The aims of this project are to prove the beneficial effects of exercise (aerobic and resistance) on spatial cognition in older adults (CU), MCI and mild AD, to understand the mechanisms of this effect, to use devices (AI) to precisely assess spatial navigation ability and to improve the compliance and fidelity of the exercise program. The key manipulable parameters of exercise training are so-called Frequency, Intensity, Time and Type (FITT).

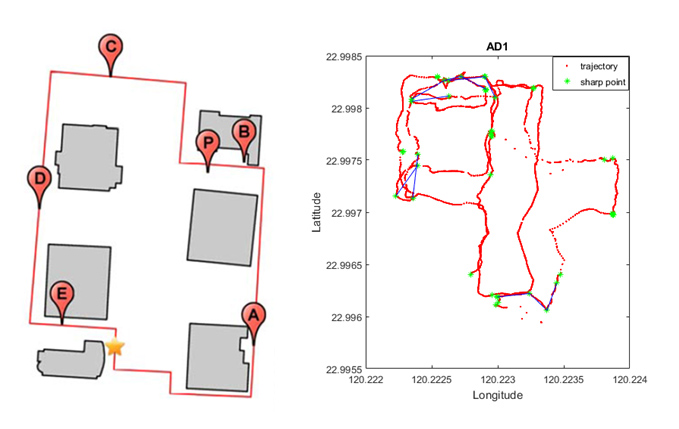

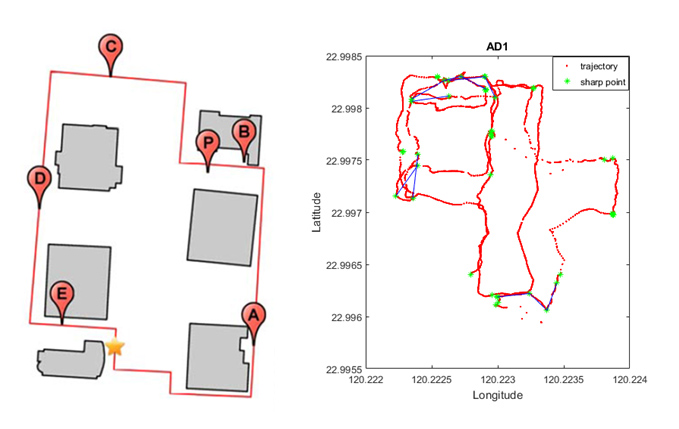

At the baseline, the spatial navigation ability or sense of location differentiates the project participants of varied clinical severity in AD adequately, as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1 (left): A map of the test field shown on the Pai-Jan device is the Tzu-Chiang Campus at National Cheng Kung University. The red line shows the contour of the designated path, and each participant walks from the yellow star point and follows the red line back to the same point. The red balloons A to E are the check points for orientation tests, and the red balloon P depicts the location of a specific participant. We measured the deviation between P and B in meters, for example, indicating sense of direction. Figure 2 (right): The trajectory of the recorded location of a participant who got lost during the test is an AD patient.

Figure 1 (left): A map of the test field shown on the Pai-Jan device is the Tzu-Chiang Campus at National Cheng Kung University. The red line shows the contour of the designated path, and each participant walks from the yellow star point and follows the red line back to the same point. The red balloons A to E are the check points for orientation tests, and the red balloon P depicts the location of a specific participant. We measured the deviation between P and B in meters, for example, indicating sense of direction. Figure 2 (right): The trajectory of the recorded location of a participant who got lost during the test is an AD patient.

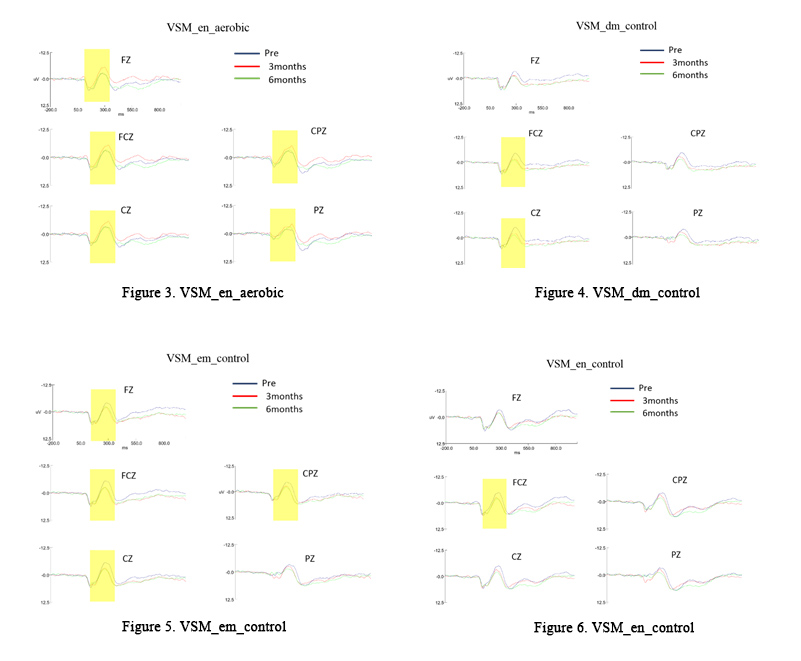

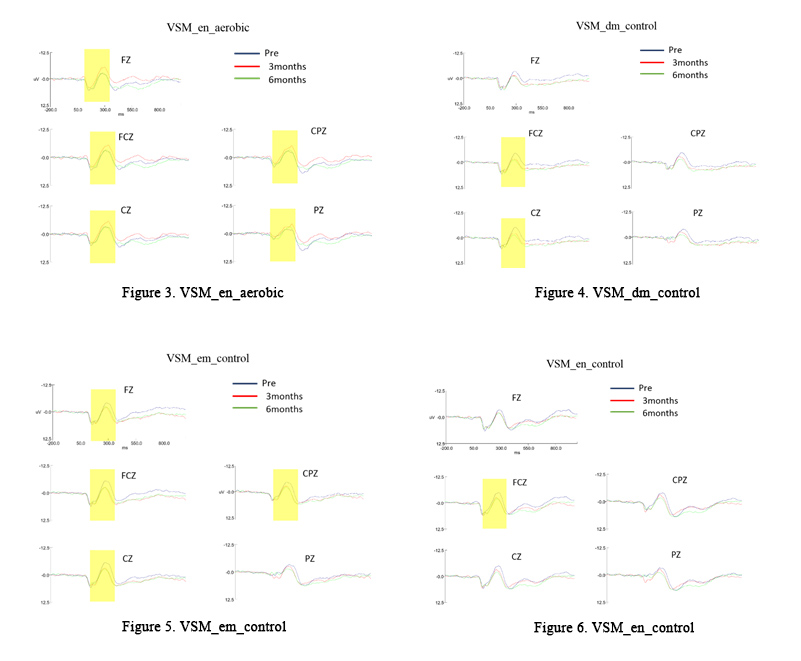

In previous studies, researchers found that regular exercise intervention improved cognitive functions in older adults and people with MCI. We adopted a similar protocol and prescribed an exercise regimen. Exercise types are either aerobic alone or combined aerobic and resistance, the duration is 30 minutes per time, and the frequency is three times per week. The duration ranges from 3 to 6 months. We used the Pai-Jan device to assess sense of location and event-related potentials (ERP) to assess spatial cognition. Structural and functional MRI, serum Aβ, tau levels, and hormones (e.g., testosterone and neurotrophins or exercise-induced effective factors, EXiEFs) were also used to analyze the effect of the exercise intervention. As shown from the preliminary interim analyses, exercise exerted beneficial effects on spatial cognition, in particular for the ADFH and MCI groups, as indicated in Figures 3 to 6.

Figure 3: for the aerobic group, the amplitude revealed significant main effects of the Fz, Fcz, Cz, Cpz and Pz in the icon-easy condition. Figures 4-6: for the control group, the amplitude revealed significant degeneration of the Fcz in the icon-easy condition, the Fz, Fcz, Cz, Cpz in the con-easy condition, the Fcz, Cz in the con-difficult condition. No significant main effects for the resistance combined with the aerobic exercise group.

Figure 3: for the aerobic group, the amplitude revealed significant main effects of the Fz, Fcz, Cz, Cpz and Pz in the icon-easy condition. Figures 4-6: for the control group, the amplitude revealed significant degeneration of the Fcz in the icon-easy condition, the Fz, Fcz, Cz, Cpz in the con-easy condition, the Fcz, Cz in the con-difficult condition. No significant main effects for the resistance combined with the aerobic exercise group.

Since many people with a family history of AD would worry about their increased risk of following their parent or parents to have AD in the future, something should be done. In this project, we have been working on the role of genetic polymorphism on human spatial cognition, setting a tailor-made exercise training program by using AI to improve spatial navigation ability and finally to solve the puzzle of the causes why people get lost.

Acknowledgements: Joyce Chou, Shau-Shiun Jan, Chia-Liang Tsai, Chun-Yu Lin, Yu-Min Kuo, H. Sunny Sun. Part of the research results had been published in journals, including Current Alzheimer Research, NeuroImage: Clinical, PLoS ONE, Gerontechnology and Alzheimer & Dementia (suppl).

References:

Tsai CL, Ukropec J, Ukropcová B, Pai MC. Distinctive effects of aerobic and resistance exercise modes on neurocognitive and biochemical changes in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Current Alzheimer Research 2019; 16(4): 316-332.

Tsai CL, Ukropec J, Ukropcová B, Pai MC. An acute bout of aerobic or strength exercise specifically modifies circulating exerkine levels and neurocognitive functions in elderly individuals with mild cognitive impairment. NeuroImage: Clinical 2018; 17: 272-284.

Pai MC, Tsao SH, Jan SS. Sense of location in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Gerontechnology 2016; 15(suppl): 114s.

Pai MC, Lee CC. The incidence and recurrence of getting lost event in community-dwelling patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A 2.5-year follow-up. PLoS ONE 2016; 11(5): e0155480.